Grappling with Complexity

The field of mental health science is expanding at an extraordinary pace. This presents significant opportunities to address the knowledge and treatment gaps we face today. However, with so much complexity - spanning animal and human models, different scientific disciplines, and diverse perspectives from around the world - how do we make sense of it all? How can we overcome fragmentation, and avoid hyper-specialised silos of knowledge? Most importantly, how do we build a mental health science that truly works for the people who need it the most?

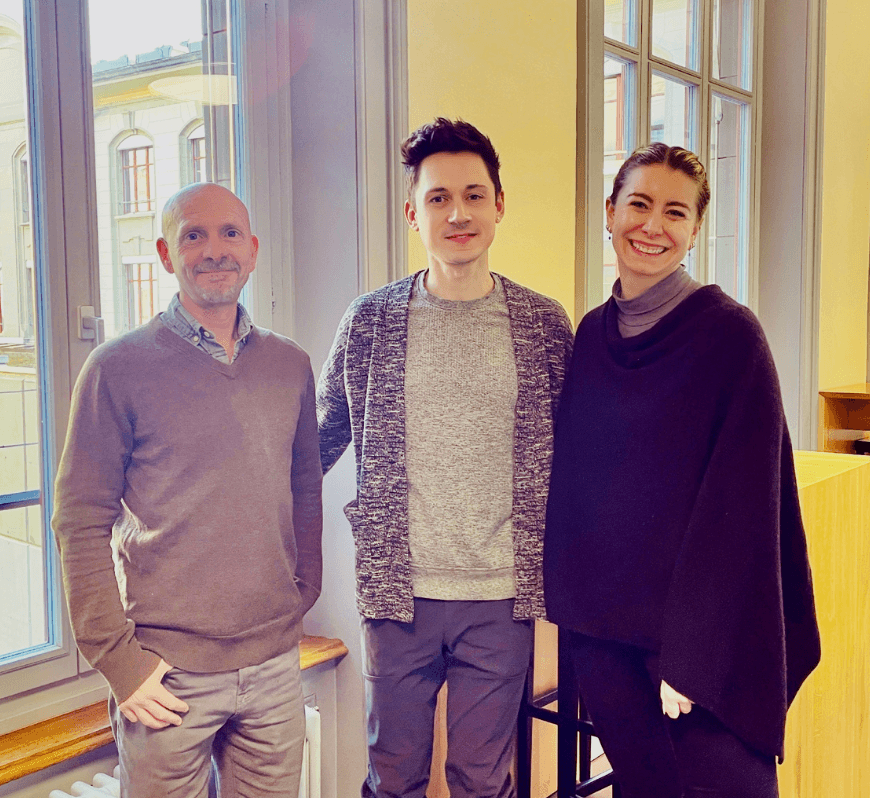

Through my role as an ambassador for MQ Mental Health Research, I’ve had the privilege of participating in projects like GALENOS, which creates ‘living systematic reviews’ of the most up-to-date findings on important topics in mental health science. Most recently, I joined the GALENOS team in Bern, Switzerland, working on the next living systematic review of research into circadian disruption and mood disorders. Alongside animal study experts, clinicians, and academics, I was invited as someone who has lived experience of these conditions and expertise in co-produced research.

Taking part across two days of meetings was an incredible opportunity to engage with cutting-edge research, but it also prompted reflection on the complexities of knowledge creation and how we can make research truly meaningful for those it seeks to benefit.

How Well Does Research Perform, and For Who?

It’s simply not enough for science to come up with promising ideas; we need to move towards performance. As someone who has experienced significant negative impacts arising from a lack of understanding and effective treatment for mental illnesses I’ve had, I believe that the success of mental health research needs to be measured by its real-world impact, and how well it bridges the gaps between research and practice, and between promise and performance.

How we go about addressing these gaps raises a vital question: who gets to decide? Who defines the research questions, sets the priorities, and interprets the results? Who gets to decide which treatments work, and what we know to be true?

A New Standard for Including Lived Experience

Historically, these decisions have often been made without meaningful input from people with lived experience. GALENOS addresses this head-on by making sure that lived experience is embedded throughout the entire research process - from setting research questions and conceptualising study design, to triangulation, interpretation, and the dissemination of findings. This integrated approach serves as a model of how co-production with lived experience can work, given sufficient time, effort, and resources. However, despite general agreement in the field of mental health research that the knowledge that comes from subjective experience is valuable, there is still little consensus about how to operationalise co-production within the context of different research projects.

In Bern, I gave a presentation about the importance of including lived experience perspectives - not just why it matters, but how we can make it a reality. I was delighted that many people attending said that they found the concepts and examples of participatory methods I shared were useful for thinking about how to co-produce their own projects in more meaningful ways.

Co-Production for Everyone

During the meetings in Bern, I was struck by how co-production not only transforms collaborations with people who have lived experience but also has the potential to revolutionise how researchers from different disciplines work together. In a field as intricate as mental health science, where specialisation often leads to knowledge silos, co-production provides a pathway to connect fragmented expertise. It encourages professionals to think beyond their immediate focus and consider how their work integrates into a broader, collective understanding.

What stood out most was how co-production invites us to embrace complexity rather than shy away from it. Triangulation - synthesising insights from different perspectives - is an essential method here. It allows for disagreement while respecting diversity, fostering a collaborative environment where no single viewpoint dominates. This isn’t about finding a single truth but about enriching our understanding of mental health by weaving together varied ways of knowing, from laboratory findings to lived experience.

The Importance of Process

I came away from Bern more convinced than ever that the way we approach research is just as critical as the results we produce. Building inclusive, equitable spaces where everyone feels able to contribute isn’t an optional extra - it’s fundamental to making research meaningful. This involves careful attention to relationships, ongoing dialogue, and constantly asking which voices are being attended to, and whose are missing. These efforts may be time-intensive, but they’re essential for creating research frameworks that reflect the complexity of mental health itself.

Crucially, this process demands a redistribution of power in knowledge creation. When people with lived experience are included as equal partners, their insights anchor the work in real-world relevance. Sharing power doesn’t diminish the contributions of academics or clinicians - it strengthens the entire endeavour by ensuring that the knowledge we produce is both inclusive and impactful.

Towards an Integrated Mental Health Science

There is much that the academic and clinical worlds can learn from co-production as it is currently practised with lived experience. Participatory approaches offer a model for how we might address the significant gaps in mental health science - not by erasing differences but by embracing them and building relationships grounded in mutual respect and shared purpose. I saw this in action in Bern. Taking part in GALENOS has given me hope that by working together - across disciplines, perspectives, and experiences - we can not only grapple with the unknown but also build a mental health science that truly performs for people who need it most.

By embracing these principles, we can turn complexity into opportunity and make mental health science truly transformative.